- Cicero, Against Verres I

Against Verres I isn't so much against Verres as it appears to be against the rampant corruption of the Roman courts.

Some "History of Ancient Rome" music for interested audiences...

Against Verres I is a powerful piece that has helped me understand both Cicero's reputation and the factors that may have contributed to his death.

The Penguin Classic version provides an introduction which helps the reader better understand the circumstances of the trial. Sadly, the introduction includes the outcome of the trial. Thus, you know the result of the argument before having read it - a bit of a spoiler. I won't do that to my audience.

Run Up to the Trial of Verres, Governor of Sicily

Verres had committed many crimes against the Sicilian people, not the least of which was embezzling and extorting 40 million sesterces.

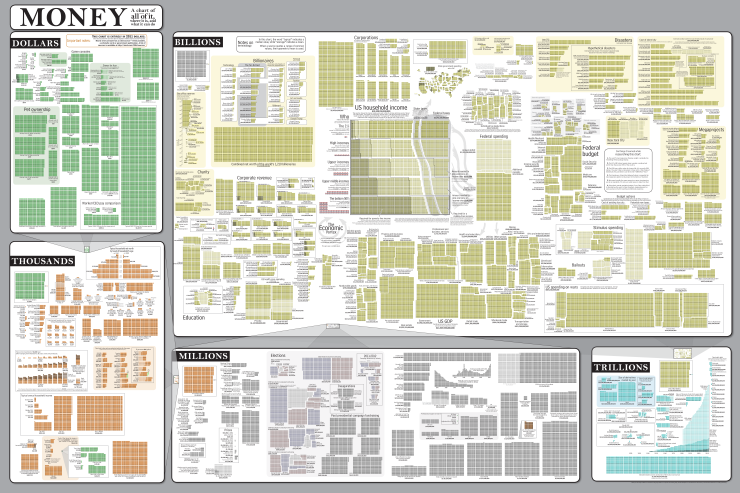

Sidenote: Tried to get the weight of 40 million sesterces of silver, as 40 million sesterces should be about 10 million denarii. Answer: it varied, but a good estimate might be 1,000 kilograms of silver. Which, of course, is utterly meaningless in modern currency: 1,000 kg of silver is only worth about $1 million USD. This is the problem of conversion between cultures with vastly different levels of technology and currency systems. Fiat currency vs. a gold or silver standard alone is a problem, as can be deduced from this XKCD ( http://xkcd.com/980/ ):

Long story short, 40 million sesterces is "a lot of money."

Stealing vast sums of money from a province was a tradition of Roman governors, but Verres apparently went well beyond the "good taste" levels of theft expected. Like moral system so many characters in The Godfather, "wetting your beak" was expected, but not to the detriment of the family, the province and Rome.

Because Roman senators were often next in line to get a province to govern - and all the associated juicy tidbits - it was very difficult to convict a governor of malfeasance. Juries were made of senators under Sulla and the senators were hesitant to rule against behaviors that would benefit them in the near future (I find myself thinking back to the cited song above...)

Like today, it was possible to completely derail the trial process through tricks of procedure. Verres went to ludicrous extremes attempting to delay and prevent his trial - or assure the outcome. For one thing, he tried to get a prosecutor that he trusted in Cicero's position.

As I mentioned before in this post, Rome didn't have a real "criminal justice system" as we think of it today. There were no police and there definitely wasn't any district attorney. If you wanted to have your case heard you needed a sort of champion for your cause in the Forum.

In the trial of Verres, Cicero was "championing" the people of Sicily. This wasn't 100% due to simple goodwill. Cicero had been a quaestor in Sicily. A quaestor was a type of very powerful upper-level aid for the governor. During his term in office, Cicero had accumulated favors with various notable Sicilians which had to be repaid. (Note: I think back to Mario Puzo's "The Godfather," which is a very good book.) Thus, by taking up the case, Cicero was not only repaying his favor-debts to others but accumulating favor-debts that would have to be repaid.

Verres tried to place others in the role of prosector for his case. One way he did this was by claiming that where Cicero needed 110 days to accumulate evidence, his prosecutor would only need 108 days. Cicero hamstringed this by subsequently claiming he could prepare evidence in 50 days, an astoundingly short period of time given the complexity of the case and the distance that the witnesses and information had to travel.

One interesting point I learned from all this finagling was that a prosecutor in Rome didn't just argue the case in court. They actually acted a bit like a private detective service, gathering evidence and interviewing witnesses themselves.

Another trick that Verres tried to pull was to try and place the trial after the various games that were scheduled to take place in the fall. Pompey was hosting 15 days of votive games and immediately afterwards were the ludi Romani, the great Roman Games, which would last for another several weeks. All together the games threatened to delay the trial by 40 days.

Other procedural tricks were attempted and subsequently thwarted by Cicero's equally devious maneuvering. Eventually the trial commenced on a schedule that really benefited no one: Cicero had ten days to present his evidence before the trial, there would be a break for the games, and then the trial was scheduled to continue.

The argument is part of the opening argument in court. The sequence of events in a Roman trial was:

(1) Prosecution outlines the charges in a major speech; this is what the document Against Verres I provides. It's a record of Cicero's outline for his prosecutorial argument.

(2) Defense outlines its evidence in a similar manner

(3) Witnesses are called and cross-examined

Against Verres I

(First, just a neat note: apparently the Romans always numbered their published documents in verses like we see in the Bible.)

Cicero immediately plunges into his argument as an example of Roman corruption in general and implies that his audience - the jurors - are either as disgusted by the current state of affairs as he is or they, too, are corrupt:

"These days one can hear it everywhere... our current courts will never convict a rich man no matter how guilty he may be... Jurors, cheered on by a hopeful Roman people, I undertook to act in this case, not to increase the hatred of our class, but to help you fight against the infamous reputation that affects us all..."

- Cicero, Against Verres I, Verses 1-2

This floored me. Based on what I had read, he wasn't just in earshot of the educated Senate class but also the entire audience of the Forum. And it wasn't just well-breed patricians in that audience. Literally all the people of Rome - not just citizens, but foreigners, the poor, and so forth - could hear what he was saying if they chose to come.

Were they there? My book gives a definite "yes." For myself, I see it as very possible at least some of these low caste characters were there. There was no TV, no internet, no radio. Basically if you were interested in what happened in the city, you would go to events like Cicero's prosecution of Verres to become informed.

So one way to read his opening argument is as a cry against injustice. Another way to view it is as a very subtle warning or threat, imho, if the case turned for Verres.

Cicero then describes Verres's devious maneuvering before the trial (while, of course, neglecting to mention his own... :-) .) He also describes Verres's character before he took the position of governor of Sicily: his cowardice in war; his theft of not only public squares but temples to the gods; his early theft from trusted friends.

By the end of verse 12, I wouldn't let Verres guard a warm cup of piss let alone make him governor of Sicily. But, of course, just like in modern trials some of this is probably innuendo and exaggeration.

Innuendo plays a big role in this speech. In verses 13-16, where Cicero describes Verres's governance of Sicily, he includes that Verres is "sex-mad" (verse 13) and that:

"To be honest, I am held back by a sense of shame from bringing up his appalling lust for sexual outrages and crimes as I do not wish, by mentioning them, to increase the distress of those who were not able to keep their children and wives untouched by his kinks."

- Cicero, Against Verres I, Verse 16

(Sidenote: I am particularly pleased that the translator knows and properly applies the term "kink" in this case. "Fetish" is more often used, but is incorrect. A "kink" is a behavior or a fixation on a behavior. A "fetish" is a fixation on an object. S&M is correctly termed a kink, not a fetish, although a fixation on whips would be a fetish, not a kink.)

Cicero spends a good deal of time on Verres's disgusting hubris and general attitude. Cicero refers to how Verres had mocked the jury as controllable by his wealth (Verse 20). He brings up Verres's personal maxims related to wealth: that "only men who have stolen enough just for themselves should be afraid" and "nothing is so sacred that it cannot be corrupted, nothing so well guarded that money cannot capture it" (Verse 4.)

Once again, I take this with a grain of salt: it's Cicero's job to make Verres look like the greatest villain that ever entered Rome free from chains. Therefore, Verres may not have said these things. However, the jurors who Cicero was trying to move knew Verres personally. Was there some truth to this? A great deal of time is spent providing evidence that Verres not only has these attitudes but has them above and beyond what is seemly and respectable. Maybe Verres really was revoltingly hubristic even among men who believed they were descended from gods.

Cicero spends some time describing the "honorable natures" of the jury and asking them to vote their hearts and tendency towards virtue than allow corruption to fester in the courts. He describes the virtues of several particular jurors (Verses 29-30.) However, he then turns around describes the sorry states of the courts:

"... I shall lay out with definitive evidence all the wicked and criminal verdicts given over the ten years since the Senate gained control of the courts. I shall tell the Roman people why during the fifty years the equestrians were in control of this court there was no trial where there was even the slighest suspicion of cotes being sold for money. And why, after the Senate gained control of the courts and the Roman people lost their power over all of you, after his conviction Quintus Calidius said that a jury could not in all decency convict an ex-praetor for less than 3 million sesterces..."

- Cicero, Against Verres I, Verses 37-38.

Most of the remaining verses - Verses 39-56, or almost half of the text - deal with this general corruption in the courts. Cicero pulls no punches; he speaks of bribery and the corruption of juries, not just in the case of Verres but in general. With a strange prescience, Cicero says:

"... I would rather lay down my life than the energy and perserverance needed to pursue [a corrupt juror's] shameless behavior..."

- Cicero, Against Verres I, Verse 50.

Result of the Trial [Spoilers]

In the end, rather than be tried Verres ran like a bitch. Just after the first arguments and the testimonies of the witnesses for the prosecution ended the games began. Verres used this as an opening to flee to Massilia, which is where Marseilles, France is today.

(I personally know Marseilles as the home of storybook character Edmond Dante, the Count of Monte Cristo. Now I know it's where ancient wealthy Roman fugitives hid. But I digress.)

Eventually Verres's luck ran out. The same series of proscriptions by Antony that nailed Cicero resulted in the assassination of Verres as well.

To those who say that Game of Thrones or The Godfather are twisted tales of revenge and political plotting, I say: "History of the ancient Romans. Will blow your mind and it really happened."

---

Other articles in this series:

Cicero's "In Defense of the Republic": Introduction (Part 1 of many)

No comments:

Post a Comment